[Right-up] Reflections on Going Viral: What I learned from being featured by the online troll machine -by Cecilia Lero

Reflections on Going Viral: What I learned from being featured by the online troll machine

by Cecilia Lero

I’ve spent the better part of the last decade working with and among inspiring leaders from urban poor communities on various issue like housing, health, education, and gender-based violence. I’ve also spent the better part of the last 15 months witnessing the devastation that has resulted directly from the government’s out-of-control, violent obsession with drugs. I’ve had the honor of knowing just a drop of the real people and families who have been victimized. Their stories play and replay on loop in my mind. Their words ring in my ears. Their faces burn behind my eyes when I try to sleep.

On September 21st, I attended the UP-CHR rallies with a sign on my chest that said: “I am drug user. Papatayin mo ba ako? #BreakTheStigma.” There were three reasons why this was the message I chose: First, to challenge the stereotypical image of a drug user. Second, to humanize drug users. I truly fear that we are becoming numb to the death around us, and that victims are reduced to statistics and superficial tallies of how “good” or “bad” they supposedly were in life. While Kian and Carl are jarring reminders of the multitudes of people not involved in drugs that have been killed, it is important to remind people that even drug users, and yes, even addicts, are human beings that should not be killed by the state. Third, I hoped to inspire others to stand in solidarity with the overwhelming majority of drug users who are not the violent threats to society this government would have us believe.

I wish I could say I had a fourth reason. I wish I could say that I hoped to inspire actual drug addicts and dependents to come out and seek treatment (as opposed to casual users who don’t need treatment – more on this later). But, for as long as the state encourages killing, I can’t do that in good conscience.

I was not the first to take this approach. In July last year, then-19-year-old Adrienne Onday bravely went about her normal commute with a sign that read “LAHAT TAYO POSIBLENG DRUG USER.” Numerous student and youth groups around the country have staged “die-ins” where they lay in public spaces with cardboard signs mimicking the cadavers that have littered our streets.

Nevertheless, on the evening of September 21st, I started receiving worried messages from friends. A pro-Duterte propaganda page had shared my photo with the hashtag #ManlabanParaSaKarapatanNgMgaDurugista. By the next evening it had been shared by other pages and garnered over 8,000 reactions, at least to this author’s knowledge.

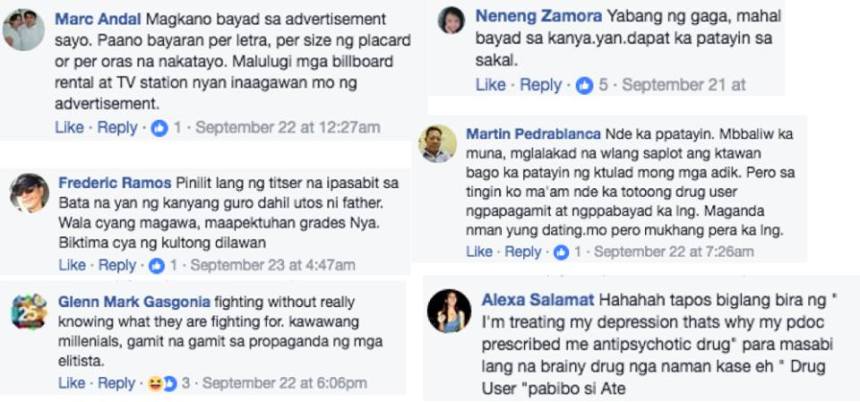

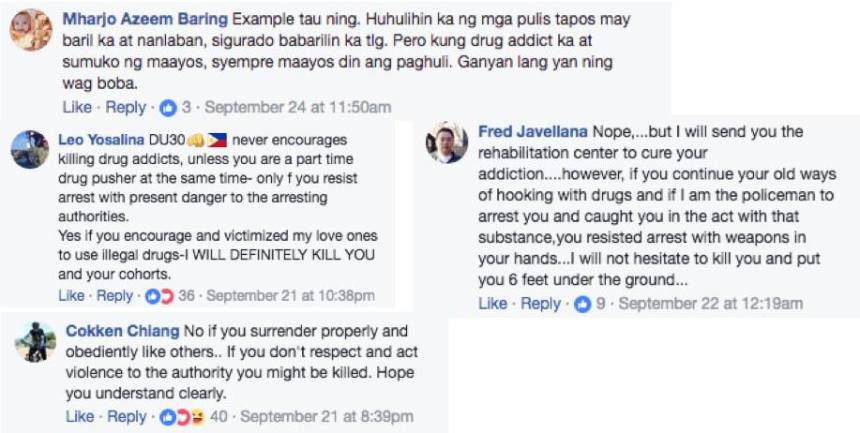

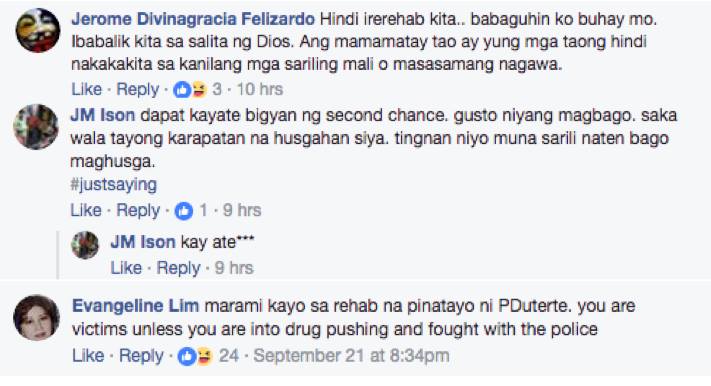

After the initial shock, I was found myself tickled that the pro-Duterte propaganda machine had helped me get the message across. After all, the point was to make a shocking statement. However, I knew that, given the context of where the photo was shared, many reactions would be full of violence and vitriol. Preparing myself for the worst, I dove into the comments sections. While I do not want to lump together all Duterte supporters, what I found has helped enlighten my understanding of the way the most zealous drug war-defenders think. The following are some common reactions and my observations:

1) “Magpa-rehab ka”

I entered the comments section of pro-Duterte propaganda pages expecting to see an overwhelming majority saying “Yes, you should die.” But, I was actually surprised and heartened at the number of avowed Duterte supporters who seemed to believe nonviolent drug users and even dependents should be rehabilitated and not killed. This reflects the seemingly contradictory survey results wherein 78% of people report being supportive of the war on drugs , and yet over 92% of people believe it is important that suspects be taken alive.

Then there were those who, while taking a less nurturing tone, emphasized that I would only be killed if I fought back or posed a threat to others.

This was a revelation to me. In this highly polarized political climate, I and other opponents of the government’s violent approach to drugs often assumed that supporters of the government’s approach were also supporters of the killings. We thought that they morally believed that the state should wipe out current and former drug addicts and casual users. Thus, many of us had given up trying to reach out to them because we thought we held diametrically opposite values.

It turns out however, that the vast majority of drug war supporters and opponents hold the same values. Both sides believe that drug addicts should be arrested and given a chance at rehabilitation. Both sides also believe that police officers have the right to defend themselves if their or a third party’s life is in immediate danger.

Where we differ is in what facts we believe. Supporters take at face value the state’s claim that deaths only happen when victims fought back. There are even those who claim that killings are not happening at all. Opponents, on the other hand, point to the President’s own words when he says, “If you lose your job, I’ll give you one. Kill all the drug addicts” and “O, pag walang baril bigyan mo ng baril.” We point to the communities who report name after name of those who surrendered and quit, but were killed anyway. We point hard cases like those of Kian, Carl, Jefferson Bunuan, Efren Morillo, Michael Siaron, Raymart Siapo, and countless others who were shot in the back, while on their knees, while handcuffed, or while sleeping, in other words, those who did not fight back.

While fake news and the selective belief in logic and facts are real problems, it is always possible to come to agreements about facts while it is nearly impossible to come to a mutual understanding when you have diametrically opposed moral ideologies. I am relieved, as it appears that Filipinos have not totally lost our moral compass. Analytical capacity, however, is something we desperately need to work on.

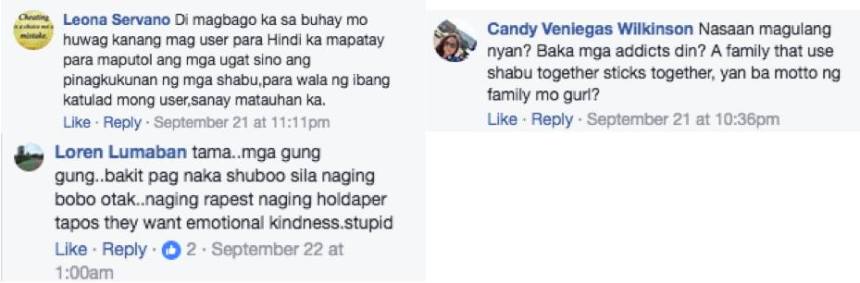

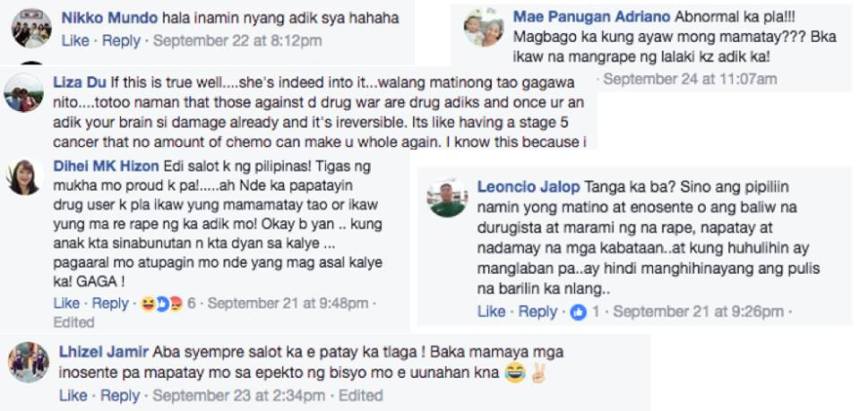

2) “User = addict = murderer/rapist”

“Drugs = shabu”

I was careful to put on my sign “Drug user ako.” And yet, so many netizens were quick to blast me for my drug addiction. Even those who nurturingly urged me to go to rehab belied their lack of understanding of the difference between a casual drug user and a drug addict or dependent.

The vast majority of illegal drug users are not, and will never become addicts. Data from a 2016 Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB) report states that of everyone who tries shabu or marijuana for the first time, 72% and 75%, respectively, will never do it again. The DDB further reported that of the 4.8 million Filipinos who had ever tried any form of illegal drug in their lifetime, only 1.8 million (37.5%) were categorized as current drug users. The DDB defines “user” as anyone who has used illegal drugs more than once in the past year. It is important to note that a person who has had two puffs of marijuana in the course of a year would be categorized as a user, but is clearly not an addict. While the DDB does not have data on addiction, worldwide data has consistently shown that only 85-90% of drug users do not become addicts .

The vast majority of people who use drugs are normal people who, to paraphrase Dr. Carl Hart, go to work, take care of their families, contribute to society, and overall live pretty normal lives. They do not need rehabilitation because they are not abusing drugs. The stigmatization and stereotype of all drug users as automatically violent, raping murderers is one that defies all reasonable logic and evidence, and takes attention and resources away from focusing on real violent criminals that hurt other people.

My sign also did not indicate what kind of drug I use. Many angry commenters assumed not only that I was an addict, but that I was specifically a shabu addict. Indeed, the President’s obsession with drugs has been almost exclusively focused on shabu. When questioned why those killed have almost exclusively been poor, Duterte said that the poor use shabu and shabu is more destructive than cocaine or heroin . He said this despite extensive scientific literature that does not support such claims.

However, police operations have also been cracking down on marijuana, the second most widely-used illegal drug in the Philippines. Despite recent progress on a bill to legalize medicinal marijuana, it continues to be a target of and justification for state violence. In the Congressional investigation about the secret Manila jail where 12 people were detained, the station chief stated that they had been arrested for “pot session.” Similarly, numerous police reports that I have personally seen from working with the victims’ families claim that operations targeted “pot sessions.” Thus, as the world and even our own laws move toward legalizing marijuana use, marijuana remains a justification for state-sponsored violence and killing.

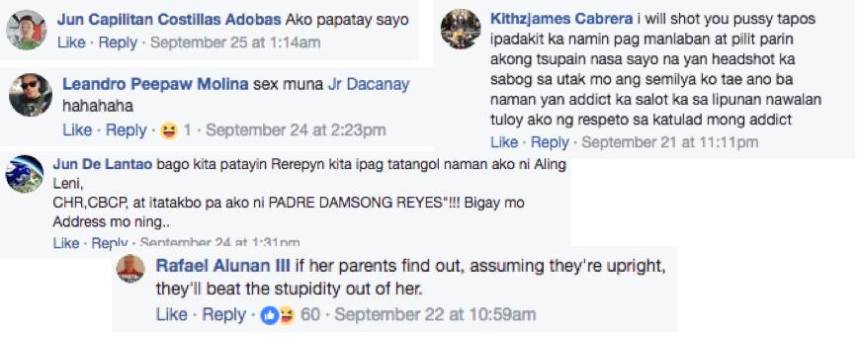

3) “Papatayin kita…sa sarap”

As expected, the comments also included many threats of violence, and especially sexual violence. Hundreds of people thought they were original and witty by saying “papatyin kita sa sarap.” Others said they would rape me before cutting off my head. A former DILG secretary, with whom I have had many friendly personal interactions in the past, instructed my parents to “beat the stupidity out” of me.

The violence that has characterized both police operations and zealots’ defenses of the government’s approach to drugs presents a paradox. Those who defend the war on drugs and the killing of drug users say that it is necessary in order to prevent rapes and murders. Yet, these comments condone exactly that: rape and murder. As the president has done on multiple occasions, these zealots are justifying and encouraging the very thing they claim to hate.

If we really care about stopping rape and murder then we are doing a disservice by focusing on drug use instead of focusing directly on rape and murder. If we are serious about preventing rape, let’s invest in a massive street-lighting and gender sensitivity campaigns. If we are serious about preventing murder, let’s invest more in the PNP’s campaign against loose firearms. Instead of mobilizing barangays to identify past and current drug users, let’s mobilize them to identify and monitor those who have displayed violent tendencies. After all, who is more likely to commit rape or murder: A student who take a few puffs of marijuana while watching a movie? A worker who occasionally takes a hit of shabu to pull an all-night shift? Or, a person who sees a picture of a girl and says “I will rape you. I will murder you.”

4) “Hindi adik. Bayaran lang.”

There were people who both defended and attacked me who refused to believe I was a drug user based on how I looked. Ironically, challenging the stereotypical image of drug users was a main point of my protest.

We cannot deny that popular images of drug users are strongly related to class. Say “adik” and the image that jumps into one’s mind is usually one of a poor, thin, dark-skinned person in tattered clothes. Our language and society are replete with unconscious ways we reinforce the unfair and inaccurate stereotype that the poor, the drug-addicted, and violent criminals are one in the same.

Unfortunately, the contempt with which society treats the poor has extended to apathy or even joy when the poor are killed. If I received comments like “hindi ka mukhang adik,” photos of real victims in slippers and shorts receive comments like “eh mukhang adik ka talaga.” In neither case do the commenters know which one of us, if either, has actually used drugs, but the assumption is that the poor person deserved to die because he was probably guilty.

These views are not limited to the middle class and rich. Sadly, many among the poor have also internalized society’s contempt. Working in poor communities teaches you that disempowerment and acceptance of bad situations help to make such situations self-reinforcing. You often hear statements like “Ganito lang kami,” as a sign of resignation. These feelings of resignation and acceptance also manifest themselves in community reactions to the killings. Even among some of the most hard-hit communities, if someone who was not known to be involved with drugs gets killed, you can hear neighbors say “Ah, baka pusher pala.” They merely accept that bad things will happen in their community and have internalized the idea that maybe they deserve it.

As someone who looks very stereotypically middle class, I have privilege. When I walk into government offices and fancy buildings, security guards smile and greet me instead of suspiciously asking why I’m there. On more than one occasion, I’ve witnessed low-ranking officers rudely question urban poor and farmers, but once they see me they start standing up straight and saying “po”. When I literally wear a sign around my neck that says I’m a drug user, even the good-natured say “no you’re not, you don’t look like it”.

And that was the point: to use my privilege to stand up for those who can’t. It is not lost on me that, unfair as it is, my appearance provides me some protection. But, for millions of Filipinos who were not lucky enough to be born with light skin and chubby cheeks, a sign like that, or an unsubstantiated whisper from a neighbor, or prior drug use that they have long stopped is enough to get them killed. We must stop treating drug users, especially those who have no tendencies towards violence or harmful crime, as “others.” They are not some underclass living on the fringes of society. They are not salot sa bayan. They are our neighbors, relatives and friends. They are potentially me. They are potentially you.

Conclusion

I suppose I haven’t addressed the elephant in the room: am I really an illegal drug user or not? It would be so easy for me to say that I am clean, that the sign was just a political statement, but alas, that would defeat the purpose. What I can say is that I have not and I do not hurt people. I am a responsible person who makes responsible, positive contributions to my family, community, and country. Drug use in no way adversely affects my personal or professional lives. No one has ever become a drug dependent because of me. There are thousands of people just like me that have been killed. There are millions more just like me. Maybe you’re one of us. Do we deserve to die?

Sources:

“Approval for Duterte’s drug war slips in Philippines.” April 19, 2017. Reuters. Available at <https://www.reuters.com/…/approval-for-dutertes-drug-war-sl…>

“Duterte’s job offer to kill addicts ‘perverse’ but unsurprising – rights group.” April 20, 2017. Asian Correspondent. Available at <https://asiancorrespondent.com/…/dutertes-job-offer-kill-…/…>

“WATCH: Did Duterte encourage killing of drug suspects?” September 10, 2017. Philippine Star. Available at <http://www.philstar.com/…/watch-did-duterte-encourage-killi…>

Hart, Carl L., Joanne Csete, and Don Habibi. 2014. “Methamphetamine: Fact vs. Fiction and Lessons from the Crack Hysteria.” Open Society Institute. Available at <https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/…/methamphetamine-da…>; O’Brien, MC and JC Anthony. 2009. “Extra-medical stimulant dependence among recent initiates.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 104(1-2). Available at <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19515516>

Ho, Alex. “Duterte explains: Why the rich are beyond reach of drug war.” August 25, 2016. CNN Philippines. Available at <http://cnnphilippines.com/…/Duterte-why-rich-beyond-reach-d…>

Hart, Carl L., Joanne Csete, and Don Habibi. 2014. “Methamphetamine: Fact vs. Fiction and Lessons from the Crack Hysteria.” Open Society Institute. Available at <https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/…/methamphetamine-da…>

All submissions are republished and redistributed in the same way that it was originally

published online and sent to us. We may edit submission in a way that does not alter or

change the original material.Human Rights Online Philippines does not hold copyright over these materials. Author/s and

original source/s of information are retained including the URL contained within the

tagline and byline of the articles, news information, photos etc